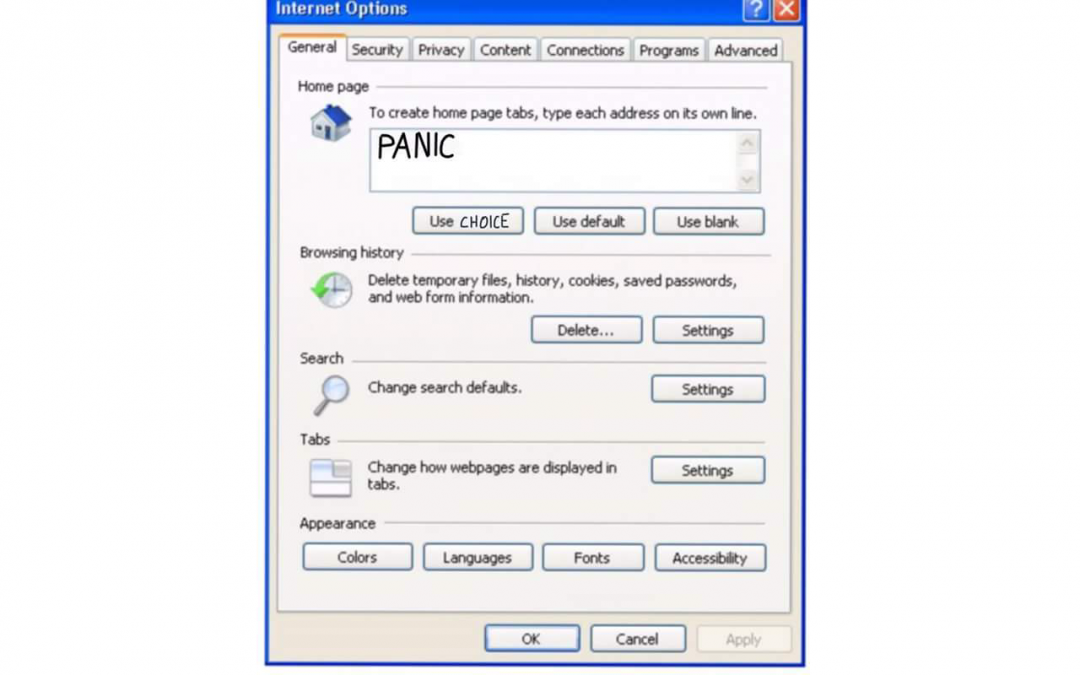

Do you panic easily? Are frequent feelings of anxiety a daily occurrence? Do you respond to challenging events with a feeling of stress? Have you offered excuses for this, by saying that it is just the way you are? Have you wondered why panic is your default response? What if, like a computer program, you were asked, ‘would you like panic to be your default response?’ Would you click OK, or would you click Cancel? So how do you stop it from being your default? What if we could just choose? In this article I briefly explain how an unhelpful response can become a default response, and how you can change it to a response that is deliberately decided and more helpful.

The Lazy Brain

‘We are all cognitive misers.’ Out of all of the university lectures that I have attended, I have remembered only one opening line, and that was the introduction to Cognitive Psychology 101. What followed was an explanation of the brain’s ability and general tendency to take the shortest distance possible in making decisions. Our brain decodes so fast – it sees a bit of information and, in a fraction of a second, it will conclude that 1 + 1 = 2.

Sometimes though, it will decide that -1 + 1 = 2, because it didn’t adequately take in the required information (I know my brain does that a lot).

Re-Training the Brain

As clever as our brain is, it is a far more challenging to re-train our brain and it takes conscious, deliberate, determined and tenacious effort. I have a chronic knee condition and an exercise was to watch myself move my leg in a vertical circle (like riding a bike). Again, and again, I would watch my knee travel out and in, mid-way through the motion and it was my job to keep it in line. I was instructed that I was re-training my brain in how the motor-neurons responded. This was incredibly frustrating as my knee would continue to do its own thing. In order to stop this pattern, I had to slow down and move my leg and knee with deliberate control. Perhaps too, the fact that I was watching my knee in the mirror, meant that my brain was watching what it was doing, and it worked.

What is the link to panic?

What has this got to do with feeling stress, anxiety and panic? To start with, it is helpful to know that feelings of stress and anxiety are all normal responses to challenging events that serve to keep us safe and alert. However, when that becomes the default response to any and every event that is in any way challenging, then it is no longer helpful for us. What can escape us in these moments is the ability to look objectively at our own reaction, recognise it as being unhelpful, and then to deliberately decide what the best response would be.

When I have discussed this in the counselling space with clients, I present to them the idea of taking control in how they respond in challenging moments. For many, it is an unfamiliar concept due to their apparent automatic responses of anxiety, stress or panic. However, we are usually able to identify contexts in which an alternate response, a calmer response, has been present; perhaps in a crowded shopping centre, or with certain friends or family members; without realising it they have been able to respond differently. It is possible, because they have done it. For some, the notion of having a different response to challenging circumstances is met with disbelief, ‘is it really possible?’ They are so familiar with feeling out of control on autopilot that an alternative seems unbelievable. The suggestion that they could learn how to be in the driver’s seat (again), is met with hope.

Know Your Brain

I then explain that the associated behavioural response to feelings of anxiety, stress or panic, is simply the brain doing what it is that brains do – it is taking the shortest distance between two points – an event and a reaction. The neural pathway has been set and it is generally strong. To change the pathway takes deliberate, conscious, and determined effort. But it can work. Remember when you were learning how to drive and how much concentration and effort it took? It’s going to be like that. Re-training your brain to respond differently to feelings of anxiety, stress and panic is hard work, but it can be done.

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT)

I’ve been ‘practising’ Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for several years now. When I say ‘practising’, I mean working on developing my own skill to respond helpfully to feelings of anxiety, stress and panic. As an ACT therapist, it is my delight and privilege to journey with people, helping them to move into the driver’s seat of their own emotional responses (referred to as psychological flexibility). I do love it when a client returns and says, ‘it really worked,’ and will tell me of an incident where they knew they were able to respond in a deliberate and chosen manner. They were still anxious, but they were not controlled by it. I guess you could say they have clicked ‘cancel’ on that request for the default response.

About Gwen

Gwen is a school teacher, counsellor, author and presenter. Gwen’s counselling practice caters particularly for children, adolescents, teachers and parents, as well as generalised counselling. She works with individuals in relation to mental health and wellbeing. Gwen is the author of Bully Resilience: Changing the Game. See www.equipcc.com.au for more information.

Recent Comments